The theory goes that organisational change – culture change – can take up to 4 years, but few companies these days can wait that long to see results. Incremental change (tinkering around the edges) can be an indulgence you can invest in but real, radical, transformational change needs more urgency. 6-12 months is all you’ve got if you are lucky. So why does it fail? And what do we mean by cultural change?

Organisational culture is typically described as the reasons why people do what they do in organisations. It focuses on the relationships between people and the relationships between the organisational structure and systems (context) and how these shape how people behave.

What does culture look like?

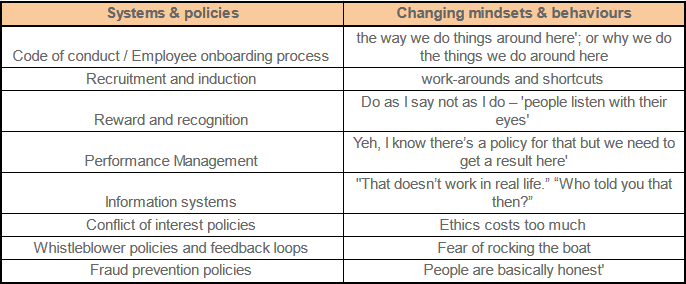

Typically there are distinctive cultures in organisations – there is the formal culture, which is the organisational policies and systems; and then there is the informal culture, which emerges as a consequence of how people respond to those policies and systems , for example, if they are adhering to them or if they find themselves, for various reasons, having to develop workarounds to enable them to get the results needed. What is often overlooked when trying to drive organisational transformation is how people are reacting to the changes being put upon them.

In an organisational transformation, the two levers of culture must be operated simultaneously. With the one hand, you are driving reforms through uplifts in the organisational systems and policies. With the other, you must also be pushing the lever on how people at the individual level must change – that’s in terms of both their mindsets and their behavioural patterns – how they make sense of what’s happening in the organisation and how they must personally change their behaviour.

Lever 1: Systems & Policies / Lever 2: Mindsets & Behaviours

To enable the first lever to be pulled effectively, a two-way feedback loop is essential. Employees need opportunities to make sense of the new policies and systems being placed upon them, but at the same time, leaders also need to understand how these policies are landing and what barriers are preventing people from understanding and embracing the changes required.

Without feedback, and without an action plan to remove employees’ perceived barriers to adopting change, new policies will not be effectively embedded into the organisation. If people aren’t responding as anticipated or experiencing change as intended, then it is necessary to recalibrate. If leaders fail to grasp that their role and new systems are not shaping new thinking as a prelude to new behaviour then apathy, resistance or sabotage might result. If employees don’t understand the role they personally play in terms of the new direction and the new behaviours expected of them there is a high risk that workarounds will persist.

Changing mindsets is the key to successful culture change

Changing mindsets is the key to successful culture change. Lever one is about having the right systems and policies, and the important part of pulling the second lever is the change story communicated to staff. It is up to leaders to drive that story: Leaders are the loudest message in any organisation, what they do gets replicated and what they reward gets replicated by leaders at every level. It’s critical for the C-suite to role model the stated values of the organisation and realign reward and recognition systems to support stated values. Leaders must take their employees with them on the journey of change, giving them an understanding not only of the path ahead, but also the reasons why change is necessary - the social context of culture.

Thrusting new ways of doing things, without calibrated and supporting change communications and a clear vision of a future state undermines employees’ trust in leaders and saps their engagement and cooperation with the changes being asked of them. The consequences of not bringing the people with you is that the old ways will stay with you. This can have dire consequences in business performance, employee recruitment and retention and customer acquisition and loyalty. Change is driven by external factors. If you cannot adapt quickly to these factors the business will ultimately fail.

Most importantly, Map the Journey

Start with a clear vision of where you want to be at the end of the change journey; at the executive level draw up a change road map identifying the obstacles to change and the timeline; identify the ‘low hanging fruit’, the quick wins (this will help people to see that you are achieving improvements); have the Board on board; and appoint high level OD (organisational design) person to drive the change.

Please fill out the form below to get in touch regarding your organisation’s needs and we will get back to you as soon as possible. You can also call us on 0430 889 850 or email us directly at [email protected].

|

|